Poet, performer, and media provocateur, John Giorno has been one of the most consistently provoking of New York artists since his works first debuted in the early 1960s. Never settling on a single mode or method, Giorno’s early poems emerged in response to relationships with Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, then later with William Burroughs and Brion Gysin, and explored the use of found images, appropriated language, and collage. Giorno then began to explore the possibilities of recorded sound, establishing entire Electronic Sensory Poetry Environments, in which poems could be listened to and simultaneously experienced by all the senses in multi-media atmospheres. These experimentations continued with the Dial-A-Poem installations at the Museum of Modern Art, and with the Giorno Poetry Systems LPs that brought the poet’s voice to record players around the world. Giorno, in his mid-seventies, is now known for his outstanding, high-energy performances of his own work.

John and I met on a springish morning in late February at his home, a series of loft studios in a former YMCA building on the Bowery. We toured the building, talking of his selected poems, Subduing Demons in America (2008), edited by Marcus Boon, and the wealth of Giorno Poetry Systems recordings that Kenneth Goldsmith has again made available on UbuWeb. Over tea, we continued to talk.

–Michael Nardone

John Giorno: So, this is where I live. There are three lofts, but this room is where I write, so I spend most of my time here. But I also do art pieces, so I have the studio downstairs. Then there’s The Bunker, William Burroughs’s former residence, which I look after, where there’s the guest room and shrine.

Michael Nardone: How long have you been here?

I’ve been here nearly fifty years! [laughs] I came in to the top of the building for a party one night and I never left. I had a friend who lived up there. And then Burroughs moved into The Bunker in 1975.

It’s interesting to think of the environments that you’ve created, that in exploring new media for poetry that you’ve been able to develop new spaces in which one can experience poetry. Whether it’s the Electronic Sensory Poetry Environments, the Dial-A-Poem, the Giorno Poetry Systems, or your high-energy performances, you have consistently explored the possibility of opening up new places of contact with poetry. Can we talk about some of these poetic atmospheres you’ve created?

Going back all those years, to 1970, to the Dial-A-Poem at the Museum of Modern Art, the MoMA is now preparing a re-installation of the Dial-A-Poem. It’s part of a show that will be opening on the tenth of May. It will be made up of eight artists who changed the use of words in art. Not the actual words themselves, but the use of words in art practice.

The telephones will have 256 selections of poems you can listen to, but, like the original Dial-A-Poem, there’s the idea that you can’t choose what you get. You just get it. You’re more likely to get a Burroughs or Ginsberg or Cage or John Ashbery poem, and there’s Emmett Williams and Jackson Mac Low, but you never know who you’re going to hear. A person asked me the other day: “What happens if I listen to a poem and I want to tell a friend to listen to it?” I told him: “Well, she can’t.” [laughs] That’s the point. What happens is, when things are really successful, you create desire that is unfulfillable. That’s what makes something work.

I look through the Dial-A-Poem line-up and the list of poets on the Giorno Poetry Systems LPs – – William Burroughs, Anne Waldman, John Cage, Allen Ginsberg, Ted Berrigan, Bernadette Mayer, Robert Creeley, Sylvia Plath, Frank O’Hara, Patti Smith, Kathy Acker, John Ashbery, Frank Zappa, Laurie Anderson – and it’s miraculous how excellent the poets are that you’ve brought together, and how good these particular recordings are. Can you talk a bit about how you curated the recordings?

I was a poet and I was here in New York in the early ‘60s. I went to Columbia in the late ‘50s, and I knew all these poets who were here. Frank O’Hara was here. Alan Ginsberg really liked my work in ’62, so he encouraged my writing. But mainly I knew a lot of artists: Andy Warhol and the Pop artists, and also Bob Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. They were true friends, my friends of preference. I liked them and they were the inspirations for what I did then. They had an idea and they did it. Sometimes it was a bad idea, but they did and moved on the next day. But every day they were making and experimenting. And then there were these poets, but I must say that the poets were no help at all. Frank O’Hara only liked you if you wrote like him. And then there’s Allen Ginsberg, who was equally as unhelpful. If you didn’t write in Allen’s style, he was not interested. So the poets were absolutely no help. When I did Dial-A-Poem and those early events with the Electronic Sensory Poetry Environments, I wanted to bring together all the poets who were here and doing great things, which was everybody. [laughs] I included everyone, therefore it was easy to curate.

I remember reading that in the first five months of Dial-A-Poem, you had over a million calls.

From all over the world.

Then, at one point, the Board of Education tried to shut Dial-A-Poem down, why?

There were these two twelve-year-old boys who kept calling Dial-A-Poem, and one time they were listening and giggling and apparently their mother grabbed the phone while Jim Carroll, who wrote The Basketball Diaries, reading a poem about these ten-year-old sisters and how they liked to get fucked. The mother was furious! She called up the Board of Education and we got cut off.

At that time, there was a really great guy named Ken Dewey who became the first Head of Media at the New York State Council on the Arts. He was an artist, a conceptual artist, so I called him and he got all of the New York State Council’s lawyers on the case, and there was this great flurry of excitement. The next day we were turned back on. Maybe I said I wasn’t going to put Jim Carrol back on, but there were other poems

I’m thinking about the fact that texts published on paper can be censored in the sense that how they enter a public domain is controllable. In the ‘60s and ‘70s, one could censor a work by creating absolutely no way for people to gain access to it. This is, of course, different now in the internet age, but it’s wonderful to imagine some young poet, in somewhere like Kansas or South Dakota, calling in and being able to have direct access to these poems and these poets, to the voice of the poet.

This phenomenon you’ve just mentioned, of access because of the internet, is, for me, the saving grace of the memoir I’ve been writing because I like to write about sex. I mean, the memoir is about my life and everything I’ve worked on. I write about everything and there are so many moments. But I also was lovers with Bob Rauschenberg, and there were wonderful times and it was fabulous sex. I can remember conversations during sex, or after sex, and so I have included many of those things. They’re key moments. And this book would be unpublishable, you know, other than some small underground press. But now, the idea that a major publisher could find the right audience and sell this pornographic book of mine is compelling me to push on and do this thing the way I want it.

Can you talk a bit about your relationships with Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, and Jasper Johns? I know they were all deeply personal relationships, but all ones that had significant impact on your writing practice.

I first started using the found image in my work during the latter part of 1961, and it was because of Andy Warhol. I watched him on a daily basis and would see why he picked an image and why he didn’t pick an image. And that’s true in regards to my relationships with Bob Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns: it wasn’t exactly that they were trying to teach me something, but I simply saw how their minds worked inside the studio. So I wrote those first found poems, and I did them because the inspiration was Andy, and maybe the other Pop artists, too. That was the main reason, this direct inspiration. I mean, I had gone to school, been in art classes, knew Dada and Duchamp, but it was seeing the mind of each of them do their work and that’s what led to those first poems.

When Rauschenberg and I became lovers in ’66, I had already, a year before, began making those collages of found images and allowing various threads to move through them. So, being with him was fascinating because he had been exploring similar methods in his work. It’s not why we were together, but he was an enormous influence to have in that year.

And Jasper and I were together for a year, in ’68 and ’69. It was the same thing. It was being present, seeing how his mind worked, being with his mind.

John, I know you’re a practicing Buddhist, and that you have been for several decades. I also know that you follow the Nyingma lineage of the Tibetan tradition, and that these lofts of yours have been central to bringing Tibetan spiritual leaders to North America. I’m curious when did you first go to India, or how did you first come into contact with Tibetan Buddhism?

What happened is that I went to Columbia. While I was studying there in the late ‘50s, there were new courses in – because they didn’t know any better – the “Oriental Humanities” and “Oriental Philosophy.” Theodore de Bary was teaching classes, and Alan Watts came on to teach occasionally. I studied this for two years, and for me there was no meditation. Zen was not my path. I was not going to the Upper East Side Zen Center. That was the opposite direction where I was going. For me, then, it was drugs. When you take LSD and you have a good trip, it’s a good trip. When you take LSD and you have a bad trip, you realize it’s not the drug, it’s your mind. And so, I began to study the mind.

Starting around 1965, I had various friends who were coming back from India who had met Tibetans there. Not Allen Ginsberg; Allen was, at that point, a Hindu practitioner. Finally, in 1970 – this is after Dial-A-Poem – I went to India, and I simply followed my nose.

Bob Thurman [one of the first and foremost scholars of Tibetan Buddhism in the west, father of Uma Thurman] was there, and he was an old friend. His wife Nena had been married to Timothy Leary, who was a friend. I had taken LSD with Leary and knew Nena before she met Bob. Anyway, we were there at the same time, so I rendez-voused with them. A few days after my arrival, Bob asked me if I would like to go meet the Dalai Lama, so I went. I received very special treatment being with the Dalai Lama and with Bob, but mostly stayed back simply to take in everything. Yet this was not my path. To make a long story short, a few months later I went to Darjeeling where I met Dudjom Rinpoche, and he became my teacher. My practice became based in the Nyingma tradition.

What was and what continues to be the draw to this practice?

It’s about your mind, working with your mind. That’s all. This is Buddhism, basically. I mean, it gets very elaborate: there are many traditions and different paths, and you must find the ones you have an affinity for, but they are focused on, mostly, working with the mind.

This is what drew me, too, towards the study of Buddhism. For a number of years, before developing an interest in poetry and poetics, I studied Buddhist philosophy…

What tradition?

I’ve been particularly focused on the Vajrayana tradition.

Congratulations!

But before this, I had grown up in a very culturally Catholic Italian-American family near Scranton.

Scranton!

Exactly.

Did they make you go to church?

Every week! And catechism.

Oh, you didn’t luck out! [laughs] But I did. I come from an Italian family – my parents were born here – and my mother was a fashion designer, so I had a nanny, and she was Irish Catholic. She made me say Our Father’s and Hail Mary’s every day. Finally, I was maybe five years old, and I said to my parents, who did not go to church, I told them: “I don’t want to do this.” And they said: “We never told you to do it. So, don’t do it.” That ended my Catholic thing. So, I was enabled to become a Tibetan Buddhist.

I remember, for me, what initially drew me towards the Vajrayana or Tibetan traditions were the elaborate meditations on the nature of emptiness, the visioning practice, the mental creation and extinguishing of these visions, the acknowledging of what one creates in the mind, but also what one has the power to clear away.

And meditation will do this. For me, it’s just about doing it. Just like an Olympic athlete, say – it’s not the best example, but it will work – you have to put in the time. You have to do it. You work with the mind in solitary retreat. That’s Buddhism at its best.

Do you still practice?

Every day!

Will you talk about how or if your poetic practice is based in your meditation practice? I’m remembering this wonderful line from a conversation you did with Marcus Boon, in which you say, “I’m not a Buddhist poet and I’m not a non-Buddhist poet.”

That’s it! [laughs]

I love that comment. And very Buddhistic: Not this, and not not this.

Well, there must be some connection between the practices, but I don’t think about it so much. In meditation, you watch thoughts arise and, in the Buddhist tradition, you don’t follow them. You see them as thoughts and then watch them dissolve. By doing this regularly, you develop – they don’t use this word – but you develop muscle. In my mind then, as a poet or as a writer, you have this trained muscle and you can grab on to the images with greater voracity, or see them more clearly. Or, in other words, focus the mind on whatever the thought is and allow it to develop. It’s all connected in the discipline of working with the mind.

Do you keep journals?

No, but I have a very good memory. I’m writing these memoirs—I’ve got, what, 540 pages single-spaced now—and, to talk about the muscle, I can remember specific details of a scene, I can remember conversations word for word from fifty years ago. Every day I remember more and more. I didn’t start out with this ability. I didn’t have a memory. The memoirs started when Andy died, and what happened was that—as happens when someone important in your life dies—you remember. I began to remember all the great moments we had, and I said to myself: “If you don’t write it down now, which is already twenty five years after, then after fifty years there will be nothing left.” So, I had to learn to write prose and I did. That’s how I developed this memory!

A lot of this book is about William Burroughs when he was still alive. I wrote this piece about 1968 when he came back from Chicago and we had seen each other and been drunk and talked on and on. I wrote a piece about this encounter and finished it. It must’ve been about forty pages long. After writing it, I went out to Kansas to see Burroughs and I set it up: after breakfast, we had more coffee and smoked a joint and I asked him about this time we spent together. I asked him the same questions I asked him on the night I had written about, and he gave the same answers! He was remembering what he thought then, and he was saying the exact things I had written down. Occasionally there was an extra word or a new adverb, but all the nouns and verbs were exactly the same as I had written it.

And with this development of memory came a change in the way I performed. In the ‘60s and ‘70s, I did these sound compositions. I started reading the compositions off a piece of paper, but then I would perform these pieces over and over. At some point, I just wouldn’t need the piece of paper. I got in the habit then of memorizing everything I would perform. I’d be on tour, exhausted as can be, yet I could remember the words and could bring back their meaning and content.

The new poem that I’ve just finished, it’s about 1500 lines. I haven’t begun rehearsing it, but I’ll start doing that soon.

You’re going to memorize the entire thing?

I will, yes, before I perform it. I did write the words after all, so they’re already there. But it’s about remembering the words on your breath. Once you do that, it’s effortless.

+

PDF.

Originally published in Hobo magazine, Summer 2012.

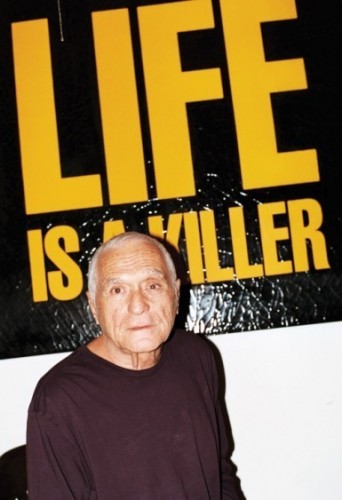

Photo by Shawn Dogimont.